Ray theory is the infinite-frequency approximation of time-harmonic wave theory. The partial differential equation governing ray theory is called the eikonal equation, which is obtained by taking the high-frequency limit of the Helmholtz equation \begin{align}\label{eq:helmholtz} \nabla^2 p + k^2 p =0\,, \end{align} where \(k = \omega/c\) is the wavenumber, \(\omega\) is the angular frequency, and \(c\) is the sound speed.

Inserting \(p(\vec{x}) = P(\vec{x},\omega)e^{i\omega \tau(\vec{x})}\) into Eq. \eqref{eq:helmholtz}, writing \(\nabla^2 = \vec{\nabla}\cdot \vec{\nabla}\), and evaluating the gradient yields \begin{align} \divergence [e^{i\omega \tau(\vec{x})} \gradient P(\vec{x},\omega) + i\omega P(\vec{x},\omega) e^{i\omega \tau(\vec{x})} \gradient\tau(\vec{x})] + k^2 P(\vec{x},\omega)e^{i\omega \tau(\vec{x})} = 0\,. \label{eq:helmholtz:1} \end{align} Taking the divergence of the quantity in square brackets in Eq. \eqref{eq:helmholtz:1} yields \begin{align} &i\omega e^{i\omega \tau(\vec{x})} \gradient \tau(\vec{x}) \cdot \gradient P(\vec{x},\omega) + e^{i\omega \tau(\vec{x})}\Laplacian P(\vec{x},\omega) \notag\\ &\quad + i\omega \gradient [P(\vec{x},\omega) e^{i\omega \tau(\vec{x})}] \cdot \gradient\tau(\vec{x}) + i\omega P(\vec{x},\omega)e^{i\omega \tau(\vec{x})}\Laplacian\tau(\vec{x}) + k^2 P(\vec{x},\omega)e^{i\omega \tau(\vec{x})} = 0\,.\label{eq:helmholtz:2} \end{align} where the vector calculus identity \begin{align}\label{eq:id:1} \divergence [f(\vec{x})\gradient {g}(\vec{x})] = \gradient f(\vec{x}) \cdot \gradient {g}(\vec{x}) + f(\vec{x}) \Laplacian g(\vec{x}) \end{align} has been used. Evaluating the gradient of the quantity in square brackets in the second line of Eq. \eqref{eq:helmholtz:2} yields \begin{align} &i\omega \gradient \tau(\vec{x}) \cdot \gradient P(\vec{x},\omega) + \Laplacian P(\vec{x},\omega) \notag\\ &\quad + i\omega\gradient P(\vec{x},\omega)\cdot \gradient\tau(\vec{x}) - \omega^2 P(\vec{x},\omega) \gradient \tau(\vec{x}) \cdot \gradient\tau(\vec{x}) + i\omega P(\vec{x},\omega)\Laplacian\tau(\vec{x}) + k^2 P(\vec{x},\omega) = 0\,. \end{align} Grouping common terms, writing \(k = \omega/c\), and suppressing the functional dependencies yields [1, Eq. (8.5.1)] \begin{align}\label{1} \Laplacian P + i\omega (2 \gradient P\cdot \gradient \tau + P\Laplacian\tau) - \omega^2 P\left[(\gradient \tau)^2 - \tfrac{1}{c^2}\right] &= 0\,. \end{align} Substituting the asymptotic expansion \(P(\vec{x},\omega) = P_0(\vec{x}) + \omega^{-1} P_1(\vec{x}) + \omega^{-2} P_2(\vec{x}) + \dots\) into Eq. \eqref{1} yields \begin{align} \Laplacian &[P_0(\vec{x}) + \omega^{-1} P_1(\vec{x}) + \omega^{-2} P_2(\vec{x}) + \dots] \notag \\ &+ i 2 \gradient [\omega P_0(\vec{x}) + P_1(\vec{x}) + \omega^{-1} P_2(\vec{x}) + \dots]\cdot \gradient \tau + i[\omega P_0(\vec{x}) + P_1(\vec{x}) + \omega^{-1} P_2(\vec{x})+ \dots]\Laplacian\tau \notag \\ &- [\omega^2 P_0(\vec{x}) + \omega P_1(\vec{x}) + P_2(\vec{x}) + \dots]\left[(\gradient \tau)^2 - \tfrac{1}{c^2}\right] = 0\,.\label{eq:1:sub} \end{align} If \(\omega\) is very large, the terms of order \(\omega^{-1}\), \(\omega^{-2}\), and higher are very small. Also, \(\omega P_0 \gg P_1\) and \(\omega^2 P_0 \gg \omega P_1 \gg P_2 \) for large \(\omega\). Thus Eq. \eqref{eq:1:sub} approximately equals \begin{align} %\Laplacian P_0(\vec{x}) + i 2 \gradient \omega P_0(\vec{x})\cdot \gradient \tau + i\omega P_0(\vec{x})\Laplacian\tau \notag - \omega^2 P_0(\vec{x})\left[(\gradient \tau)^2 - \tfrac{1}{c^2}\right] &= 0\,.\label{eq:1:sub:lim} \\ \Laplacian P_0 + i\omega (2 \gradient P_0\cdot \gradient \tau + P_0\Laplacian\tau) - \omega^2 P_0\left[(\gradient \tau)^2 - \tfrac{1}{c^2}\right] &= 0\,. \label{eq:1:sub:lim} \end{align} In the \(\omega \to \infty\) limit, Eq. \eqref{eq:1:sub:lim} separates into three independent equations: \begin{alignat}{2} \nabla^2 P_0(\vec{x}) &=0\,, \qquad && O(\omega^0) \,, \label{eq:omega:0}\\ 2 \gradient P_0 \cdot \gradient \tau + P_0 \Laplacian \tau &=0\,, \qquad && O(\omega^1) \,, \label{eq:omega:1}\\ P_0\left[(\gradient \tau)^2 - \tfrac{1}{c^2}\right] &=0\,, \qquad && O(\omega^2)\,. \label{eq:omega:2} \end{alignat} The emergence of Eq. \eqref{eq:omega:0} is somewhat surprising, since the the Laplace equation is associated with the low-frequency approximation \((k \to 0)\) of Eq. \eqref{eq:helmholtz} [2, p. 492]. Equation \eqref{eq:omega:0} is therefore superfluous to the present discussion. Do you agree?

The \(\omega^1\) and \(\omega^2\) equations, in contrast, describe wave propagation at high frequencies. The \(\omega^2\) equation [1, Eq. (8.5.3a)] \begin{align} \boxed{(\gradient \tau)^2 = \frac{1}{c^2}}\label{eq:eikonal} \end{align} is known as the eikonal equation, about which Pierce writes,

Once any wavefront surface is specified and a value of \(\tau\) is associated with it, the value of \(\tau(\vec{x})\) for any position \(\vec{x}\) can be determined by finding that ray connecting the originally specified wavefront with the point \(\vec{x}\). If the ray passes through point \(\vec{x}_0\) on the originally specified wavefront, and if \(\tau(\vec{x}_0) = \tau_0\), \(\tau(\vec{x})\) is \(\tau_0\) plus the travel time at speed \(c\) along the ray from \(\vec{x}_0\) to \(\vec{x}\).

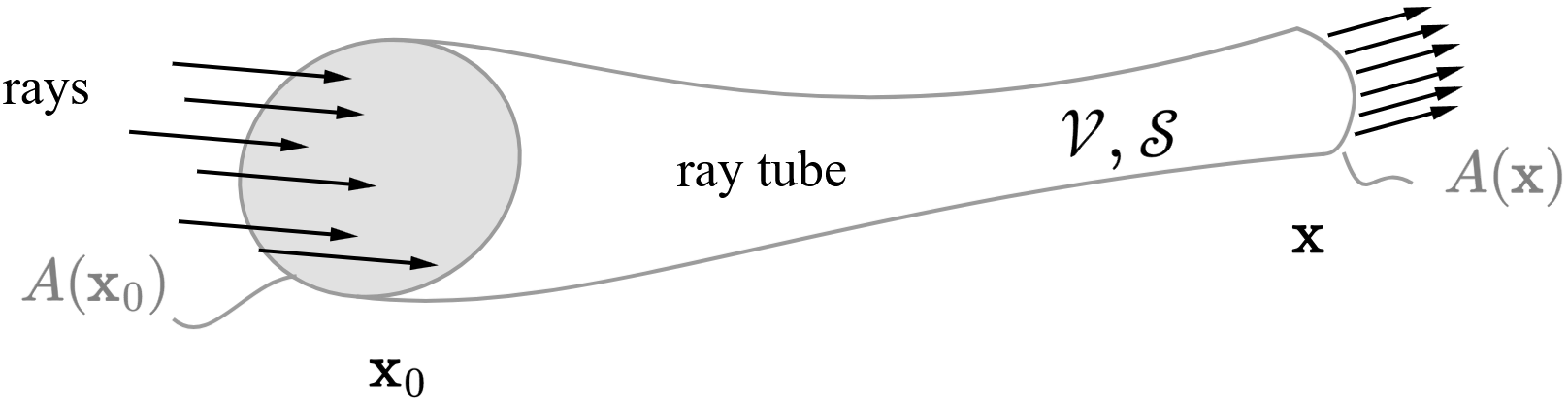

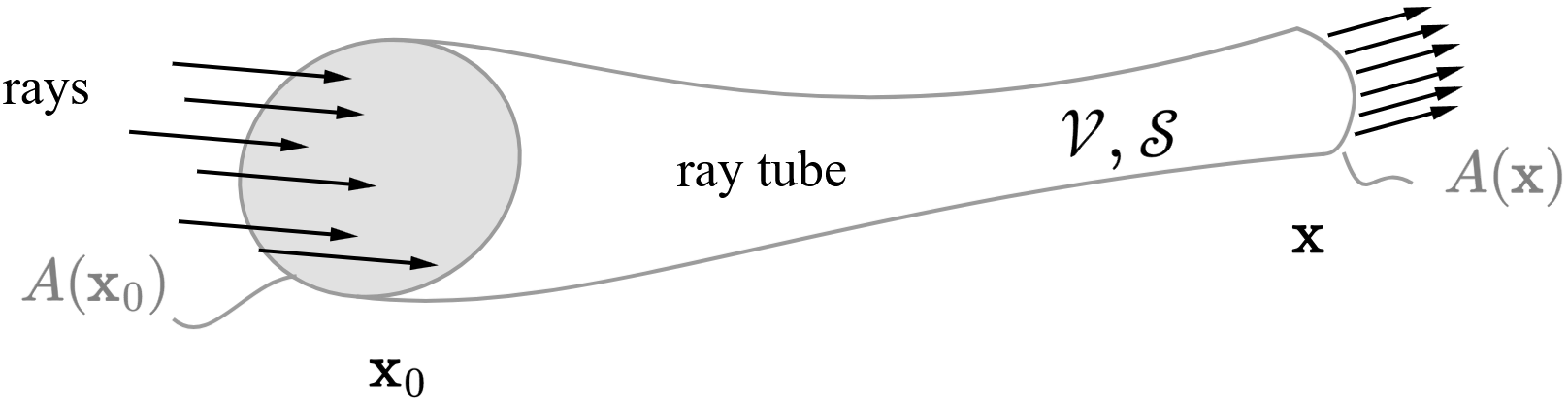

Suppose that rays in the immediate vicinity of position \(\vec{x}_0\) pass through a cross-sectional area \(A(\vec{x}_0)\) whose unit normal coincides with the direction of the rays. The same rays near another position \(\vec{x}\) pass through a cross-sectional area \(A(\vec{x})\). The areas \(A(\vec{x}_0)\) and \(A(\vec{x})\) define the ends of a ray tube whose sides are everywhere parallel to the direction of the rays. Let the volume defined by the ray tube be denoted by \(\mathcal{V}\), while the surface be denoted by \(\mathcal{S}\). Integration of Eq. \eqref{3b*} over \(\mathcal{V}\) results in \(\int_{\mathcal{V}} \divergence (P^2 \gradient \tau)\, dV = 0\), and application of the divergence theorem yields \begin{align}\label{eq:surf} \oint_{\mathcal{S}} (P^2 \gradient \tau) \cdot \vec{n}\, dS = 0 \,, \end{align} where \(\vec{n}\) is the outward unit normal vector to the surface. Since the walls of the ray tube are parallel to the direction of the rays, the only contributions to the surface integral in Eq. \eqref{eq:surf} are the values of the integrand at the ends, resulting in \begin{align}\label{eq:ray:alg} (P^2 \gradient \tau \cdot \vec{n})\big\rvert_{\vec{x}} \, A(\vec{x}) - (P^2 \gradient \tau \cdot \vec{n})\big\rvert_{\vec{x}_0} \, A(\vec{x}_0) = 0 \,. \end{align} Pierce notes that \(\gradient \tau\cdot \vec{n} = 1/c\), which is deemed to be the same at points \(\vec{x}_0\) and \(\vec{x}\). Apparently, the result to follow is based on the assumption that \(c\) is the same at points \(\vec{x}_0\) and \(\vec{x}\). But if \(c\) were indeed the same value at all points in space, then rays would all travel in straight lines, and the ray tube depicted above (adapted from Pierce's Fig. 8.17) would have no curvature. It is unclear why Pierce's Fig. 8.17 has curvature. Thus Eq. \eqref{eq:ray:alg} becomes \(P^2(\vec{x}) A(\vec{x}) = P^2(\vec{x}_0) A(\vec{x}_0)\), which, upon taking the square root of both sides and solving for \(x_0\), gives \begin{align}\label{eq:amp} \boxed{P(\vec{x}) = P(\vec{x}_0) \sqrt{\frac{A(\vec{x}_0)}{A(\vec{x})}}\,.} \end{align} Equation \eqref{eq:amp} describes how the amplitude varies along a ray tube.