The stress reflection and transmission coefficients are ratios of reflected and transmitted stresses to the incident stress amplitude,

\begin{align*}

R_\text{stress} = \frac{A_\text{r, stress}}{A_\text{i, stress}}\,,\quad

T_\text{stress} = \frac{A_\text{t, stress}}{A_\text{i, stress}}\,,

\end{align*}

while displacement reflection and transmission coefficients are ratios of reflected and transmitted displacements to the incident displacement amplitude,

\begin{align*}

R_\text{disp} = \frac{A_\text{r, disp}}{A_\text{i, disp}}\,, \quad

T_\text{disp} = \frac{A_\text{t, disp}}{A_\text{i, disp}}\,,

\end{align*}

To obtain the displacement reflection and transmission coefficients, one should start with the general relationship between stress and strain for linear isotropic media, \(T_{km} = \lambda\delta_{km} E_{jj} + 2\mu E_{km}\). Since the strain for normal incidence purely normal to the surface (e.g., purely in the \(x_1\) direction), it sufficies to consider \(T_{11} = \lambda\delta_{11} E_{11} + 2\mu E_{11} = (\lambda + 2\mu) u_{1,1} = M u_{1,1},\) where \(M \equiv \lambda + 2\mu\). For a harmonic stress wave (i.e., \(\propto e^{j(kx-\omega t)}\)), the stress coefficient \(A_\text{stress}\) is therefore related to the displacement coefficient \(A_\text{disp}\) by the spatial derivative of the displacement coefficient, i.e., \[A_\text{stress} = - jk_n M_n A_\text{disp}\,,\] where \(k\) is the wavenumber, and where \(n\) denotes the medium (\(1\) or \(2\)). However there is an additional complication: stress is defined to be positive when pushing inward. This contributes an additional minus sign to the reflection coefficient:

\[A_\text{i, disp} = -\frac{1}{jk_1M_1}A_\text{i, stress},\quad A_\text{r, disp} = \frac{1}{jk_1M_1}A_\text{r, stress}\,.\]

Thus the displacement reflection coefficient is off by a sign from the stress reflection coefficient:

\begin{align*}

R_\text{disp} &= \frac{A_\text{r, disp}}{A_\text{i, disp}} \\

&= \frac{A_\text{r, stress}}{jk_1M_1} \frac{-jk_1M_1}{A_\text{t, stress}}\\

&= -\frac{A_\text{r, stress}}{A_\text{t, stress}}\\

& = -R_\text{stress}\,.

\end{align*}

Meanwhile, the displacement and stress transmission coefficients are related by

\[A_\text{t, disp} = -\frac{1}{jk_2M_2}A_\text{t, stress}.\]

Thus the displacement transmission coefficient is off by \(Z_1/Z_2\) from the stress transmission coefficient:

\begin{align*}

T_\text{disp} &= \frac{A_\text{t, disp}}{A_\text{i, disp}} \\

&= \frac{A_\text{t, stress}}{-jk_2M_2} \frac{-jk_1M_1}{A_\text{i, stress}}\\

&=\frac{Z_1}{Z_2}T_\text{stress}\,.

\end{align*}

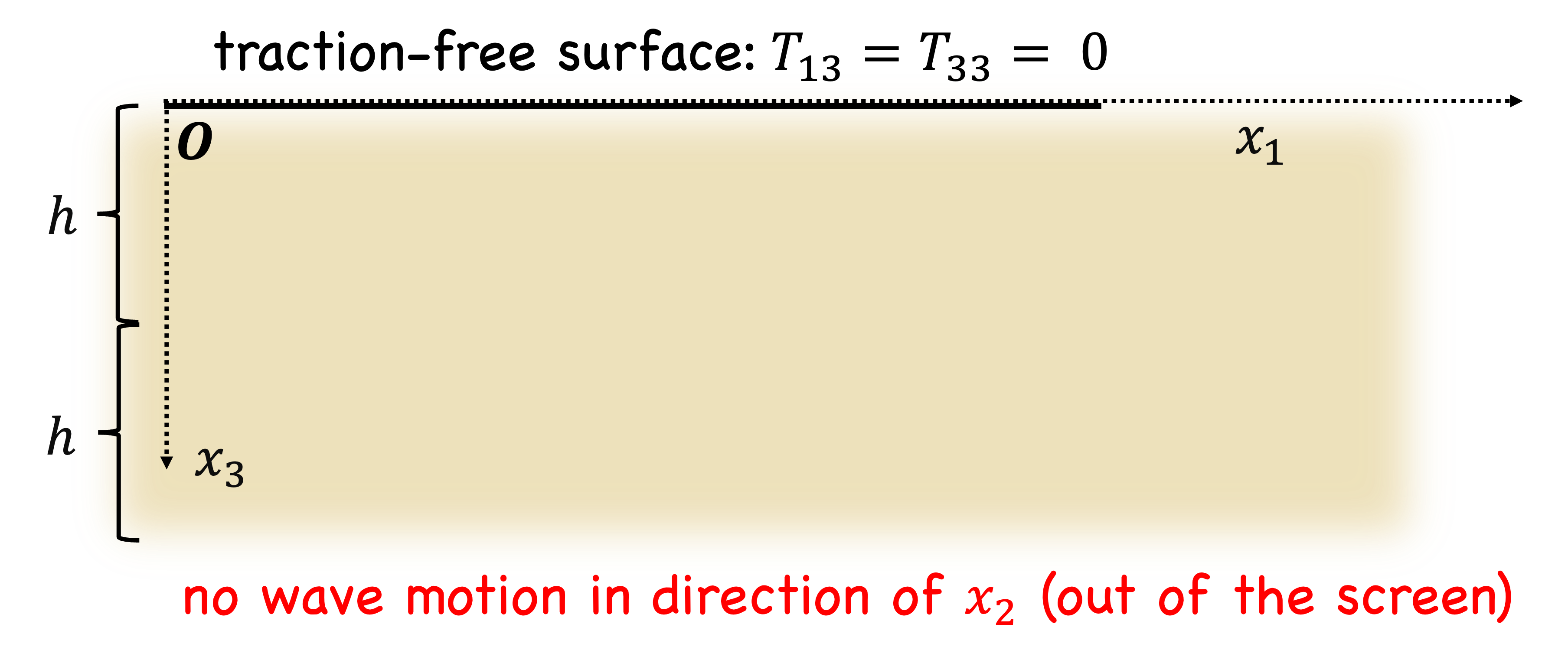

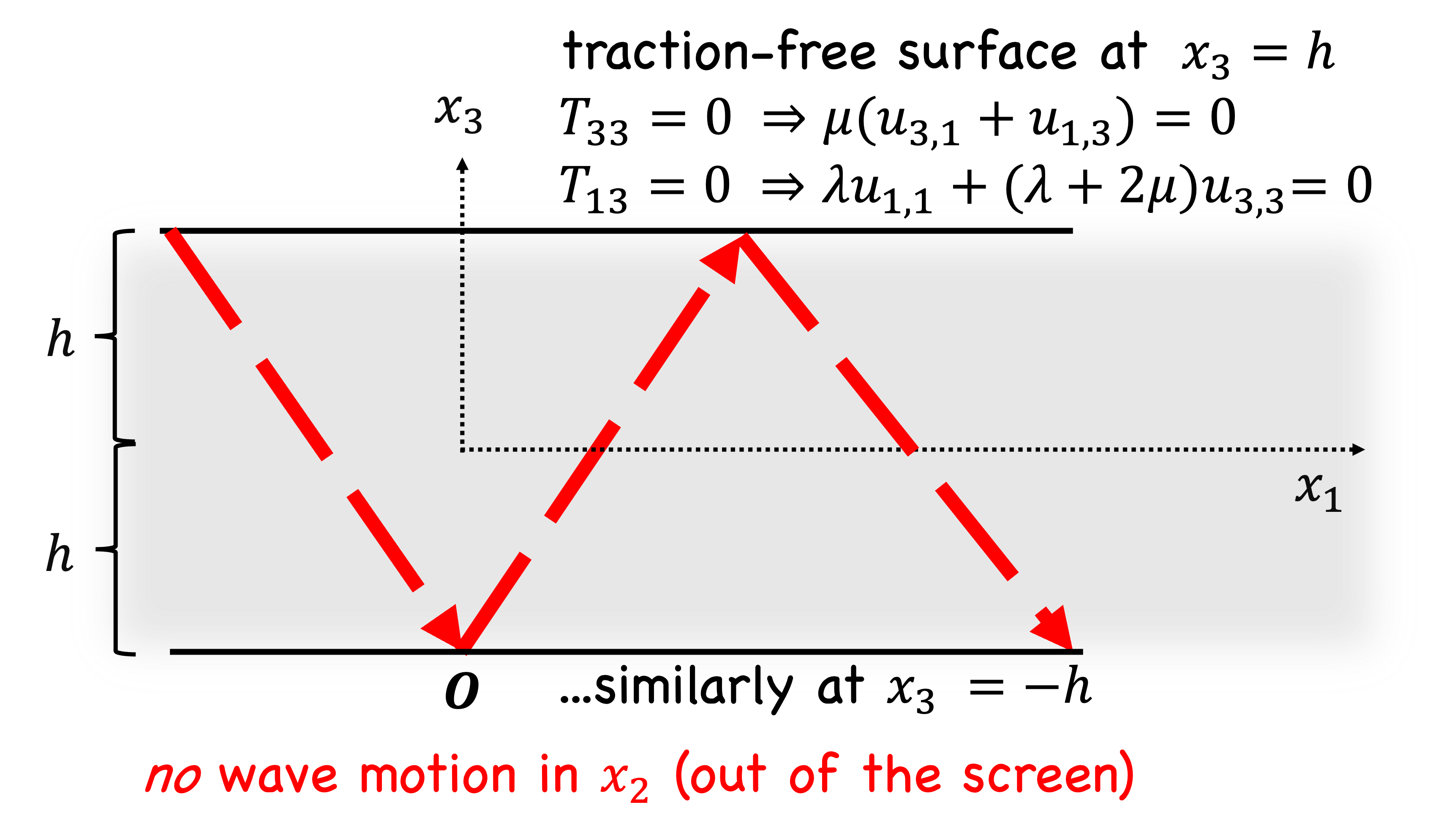

This "plane-strain" condition requires that there is no displacement in the \(x_2\) direction, i.e., \(u_2 = 0\). What are the potential functions \(\phi\) and \(\vec{\psi}\) that describe the displacement field \(\vec{u} = \vec{\nabla} \phi + \vec{\nabla}\times \vec{\psi}\)?

This "plane-strain" condition requires that there is no displacement in the \(x_2\) direction, i.e., \(u_2 = 0\). What are the potential functions \(\phi\) and \(\vec{\psi}\) that describe the displacement field \(\vec{u} = \vec{\nabla} \phi + \vec{\nabla}\times \vec{\psi}\)?

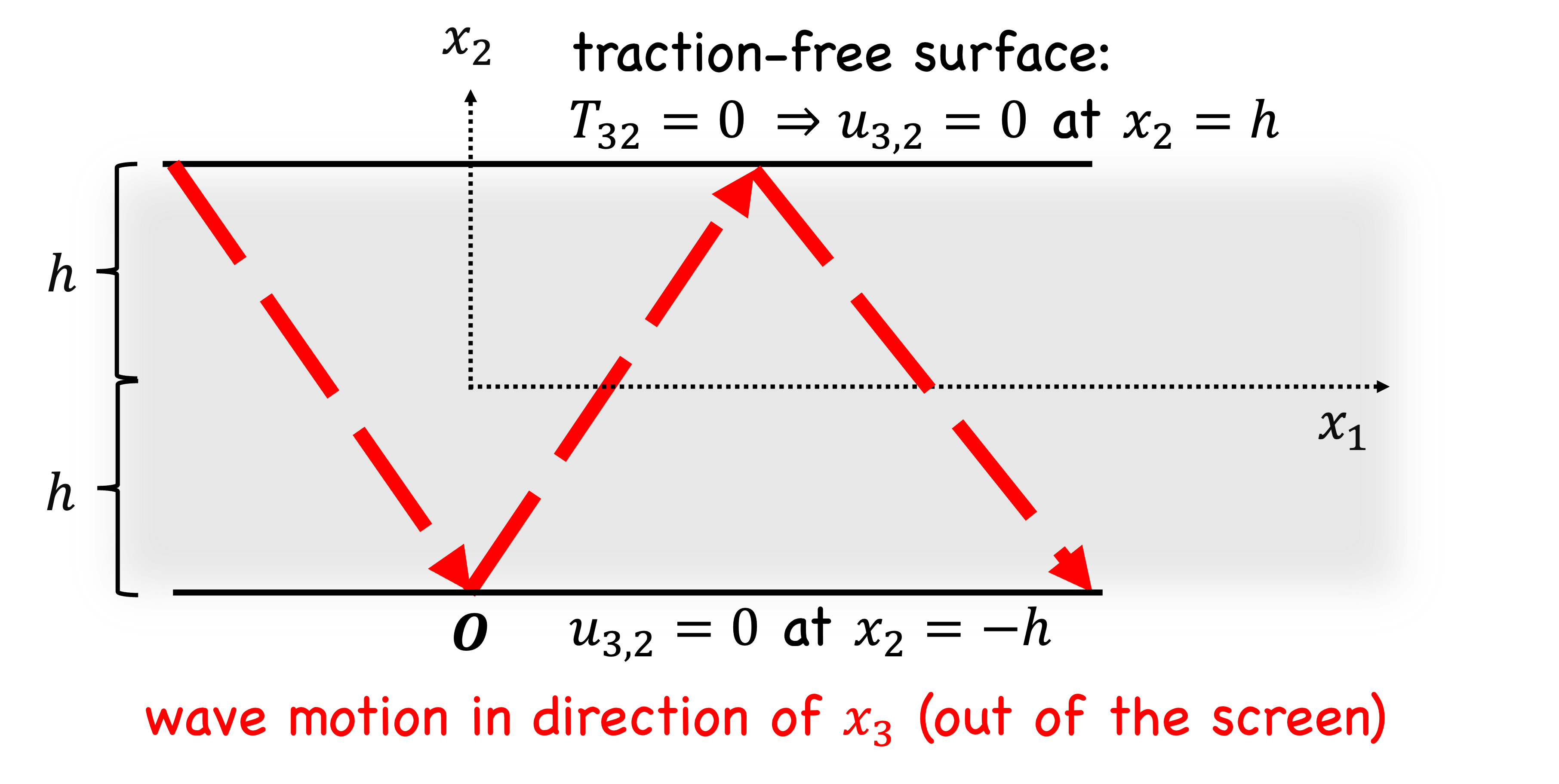

Obtain the function \(f(x_2)\), where \(q = \sqrt{k_T^2 - k^2}\). What kinds of modes does the application of the boundary conditions at \(h\) and \(-h\) give rise to?

Obtain the function \(f(x_2)\), where \(q = \sqrt{k_T^2 - k^2}\). What kinds of modes does the application of the boundary conditions at \(h\) and \(-h\) give rise to?

Limit the derivation to plane strain, i.e., \(u_2 = 0\), and do not attempt to satisfy the boundary conditions.

Limit the derivation to plane strain, i.e., \(u_2 = 0\), and do not attempt to satisfy the boundary conditions.